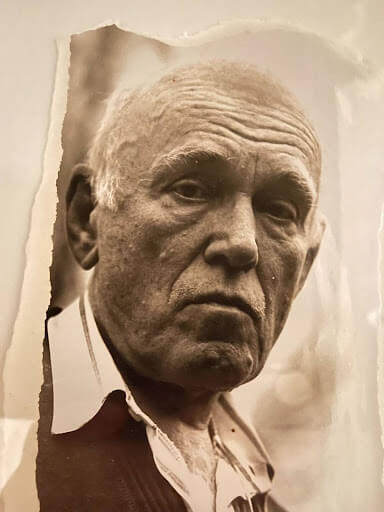

Till Janczukowicz in conversation with Svjatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Richter — he hated being photographed. But his wife, Nina Dorliac, had promised to call me if he ever changed his mind — something, she said, that happened two or three times a year at most. One evening at 10 p.m., the call came: “Herr Richter is ready for a photo.” We drove through the night. At 8 a.m., after an overnight drive, this photo was taken. We were allowed to take one. Just one. This one.

A town on the outskirts of the Ruhr area. The hall of a hotel, dark colors, subdued elegance. The unobtrusive luxury, primarily a refuge for businessmen who are planning key aspects of our cultural future in connection with a media giant, this luxury becomes irrelevant as the elevator doors open. Svjatoslav Richter steps out, holding the ancient yellowed music sheets more determinedly than the messenger carrying his briefcases. With shy but purposeful steps, he walks past the reception. His mouth corners pulled strictly downward, his feet slightly bent, he crosses the moderately busy street after looking left and right three times, lightly and somewhat awkwardly. On a three-story building, now greyed by industrial haze, it says in large white letters "Music School." Two doors. Richter climbs the few steps methodically and tries to enter. The first door is locked. He pauses in disbelief, rattles the handle again, but is still denied entry. The same happens at the second door. He returns to the hotel. I walk towards him. A physiognomy that any sculptor would fight for. The massiveness of Richter's appearance contrasts oddly with his body language, the most differentiated, subtle, and tentative one could imagine. An aristocrat with the appearance of a countryman. Never have I seen a more honest and graceful hand kiss than once from Richter.

"I introduce myself. I will accompany Mrs. Dorliac and you during your stay. Nina Dorliac is Mrs. Richter. But for Mr. Richter, Mrs. Dorliac, and vice versa. They both use formal address – a form of mutual respect that can put the uninitiated in awkward situations: We are sitting together in the car."S. R.:"Tomorrow, Jessye Norman sings. Are you going?"T. J.:"But you have a concert."S. R.:"Not you, you!"

S. R.:"I owe my musical education to three people. First, to my father. He was a musician, studied in Vienna with Ernst Fuchs. He was connected with Franz Schreker, knew Grieg, and even heard Brahms. My father was humility (he stretches the word) personified. He initially taught me, but I, still a little boy, didn't take it seriously. I was stubborn – a big mistake."S. R.:"The second person is Richard Wagner. When I was 13 or 16 years old, I played all of Wagner's operas extensively... Wagner stands above everything. Such a genius, Wagner – yes, he may have written articles, that's not so good. But the librettos are fantastic. What I don't understand about Germany is how people here speak about Wagner: his political writings don't count, they don't matter. Wagner was a superman! I can only compare him to one personality: Shakespeare. But when you listen to Wagner today, there is one thing that disturbs: conductors, performers, and directors. There is nothing worse than performers who are not on the same level as Wagner; then he becomes unbearable. Boulez conducted a pretty good 'Ring', and Furtwängler and Kleiber were fantastic. They made Wagner work. If it's badly conducted, it becomes a plague; you should stop immediately. When Kleiber conducted a six-hour Wagner performance in Bayreuth, it was as if you plugged something into an electrical socket, what do you call it?"T. J.:"With a switch?"S. R.:"Yes, exactly: when Kleiber came on stage, the switch turned on. When he left, you turned the current off. That's how it should be, otherwise, it's horribly boring, like a 'torture.'"T. J.:"Why have you never conducted Wagner? In the 1950s, you had your successful debut and farewell as a conductor with Prokofiev's Cello Concerto."S. R.:"I conducted that one time because I wanted the piece to be performed. But I don't conduct for two reasons. First: Conducting is about exercising power and striving for power. I don't like that. I hate it. Secondly: I don't feel like analyzing a score for other people. You know, it's even like this: when I go to a concert, I immediately analyze. That's why I go. I listen and immediately think how it should really be. I can't help it. Of course, I'm interested in orchestras, symphonies, etc. I don't avoid concerts because I have something against them. But when I go, I want to hear something I haven't heard before. Not the thousandth time of the 'Appassionata'...""But now isn't the time to talk about conductors, it's too late. Neuhaus, of course, was the third person who influenced me."T. J.:"You gave a piano recital before you went to Neuhaus."S. R.:"Oh yes, that was very reckless. I played in Odessa in the Engineers' Hall, in front of 300 or 400 listeners. A pure Chopin program. I don't know why I did that, it wasn't good."T. J.:"And then Neuhaus became your teacher."S. R.:"...No, not really my teacher, I only worked with him on two pieces. Beethoven's op. 110 and Liszt's B minor sonata."T. J.:"But you once said that Neuhaus made a pianist out of you..."S. R.:"Of course, Neuhaus came to all my concerts. We talked and discussed a lot about music. That's what gets you ahead. But teaching is very dangerous for one's own artistic development. It doesn't get you ahead... [Once, Neuhaus played the Tchaikovsky concerto and made a mistake at the beginning. What did he do? He kept the wrong chord throughout the entire performance!] And you know what? When the first Horowitz record came out, Neuhaus and I listened to it together with Goldenweiser. Goldenweiser was a very conservative teacher, who incidentally had a student, of whom Neuhaus said she played like a cleaning lady. So we listened to the record, and Goldenweiser said, 'My God, he plays like a whore.' Neuhaus just replied, 'Yes, but I prefer a whore to a cleaning lady.'"

S. R.:"Three composers are closest to my heart: Wagner, of course, Debussy, and Chopin. These may not be the three best, but still. Someone once said that 'La Mer' by Debussy is a miracle, like the sea itself. I completely agree... And Chopin? Only emotion counts, only emotion, nothing else! The feeling matters, everything else comes naturally. The beginning of the g-minor Ballad (Richter directs), everyone plays it too fast. It has to sound (he demonstrates). The beginning of Beethoven's 'Tempest' Sonata is also taken too quickly by everyone. It has to sound like a question, mysterious. But people no longer take the time... The most beautiful Chopin I heard was from Friedman. He had such a wonderful tone, I've never heard Chopin played as beautifully as he did."

"I ask Richter, although he dislikes such questions, which other pianists he has listened to. He thinks carefully, takes long pauses."S. R.:"I rarely go to concerts, but I've heard some records... The most convincing for me was Neuhaus. How he played the fifth Beethoven concerto, I will never forget. I've never played it myself. Neuhaus' interpretation was flawless. Rachmaninoff also impresses me as a pianist. He played very nobly. His way of playing is completely out of fashion today, but it's worth imitating. I listened to a record by Lipatti: Chopin Waltzes, Bach, and Chopin's h-minor Sonata. The Waltzes? Maybe a bit too similar. But the B-major Partita by Bach and the Chopin Sonata, that was fantastic... I also think Elisabeth Leonskaja is on the right path. She's just terribly self-critical. That's typical Georgian. I listened to a record by Michelangeli, Debussy. It was fantastic, but I didn't like it at all! Everything was good, but it felt like being in a closed room with no air to breathe... Once I heard Martha Argerich and Kremer. She's very gifted, but the two hadn't rehearsed beforehand. I once did something with Karajan and Fischer-Dieskau, and we rehearsed one page a day. And for a piano concerto, you need 15 rehearsals, that's how it should be! Do you know who is phenomenal? The pianist of the Beaux-Arts Trio. What he does looks horrible, he pulls terrible faces, but after a minute, you forget all that because he is a great musician. Initially, I was completely impressed by Van Cliburn. I've never done something like that, but I worked very hard to ensure he won the Tchaikovsky competition. They didn't want to give him the prize because he was American. He played with total commitment, gave himself entirely to the music. Every time he came to Russia, he had a huge success..."

On the way to a restaurant, we talk about Glenn Gould.

S. R.:"Gould made a strong impression on me. His Goldberg Variations are fantastic. I've heard Brahms, well, it didn't really say much. Gould plays often a bit too dry. But Bach, for example, has written so much vocal music, how can you play him like that? And what isn't proper: Gould ignores repeat signs. You just can't do that. For example, if Schubert writes repeat signs, there's something he's thinking of. And I can't take him seriously, because he said he hated Schumann, Chopin, and Schubert. That's just impossible. (Richter becomes agitated.) I can't understand him, because obviously, he loved Brahms, and Brahms wouldn't have been possible without Schumann. You know, once, I didn't read it myself, but supposedly he wrote a review of one of my concerts. I played Schubert's piano sonata D 960. Gould wrote: 'I actually wanted to leave because of the terrible program, but Richter's playing held me so spellbound that I stayed.' Well, that's fine, he can write that, but why didn't he say: 'From now on, I love Schubert?' It's incomprehensible (Richter gestures). How could he say something like that?"T. J.:"He said it because you played it."Richter stops: "But no, I only did what was in the music!"T. J.:"But you bring something of yourself to the performance."S. R.:"No, only the music text matters, nothing else."T. J.:"But when you play a Schubert sonata, the audience is captivated. If I play one, they probably won't be."S. R.:"Then you're not doing what's in the music."

T. J.:"How do you feel today?"S. R.:"37.5 degrees temperature, but I don't care. What did you listen to yesterday?"T. J.:"Krystian Zimerman with 24 Debussy Preludes."S. R.:"But you just can't do that! You can't play all 24 Debussy Preludes in one evening... maybe six. It devalues itself... For the pianist, the Preludes are easy. The Estampes are much harder... The Well-Tempered Clavier, you also can't play in one evening. I've split that over four evenings."

T. J.:"Do you think one should never dedicate an entire evening to a single composer? Arrau, for example, often played Beethoven-Liszt programs. I remember an evening with Beethoven's op. 10,3, the Appassionata, Liszt's Dante and h-minor sonatas."S. R.:"That's too much. The Appassionata must be the end of a program. No encore, finished. Moreover, you can't play the Liszt sonata with the Appassionata on the same evening. They're two completely different things. There's no balance, because you notice that Beethoven is something higher. That's how the Liszt sonata gets devalued. For example, you can play an entire evening of Schubert, or Bach. That works... What can you play before the Appassionata? Maybe Mozart. But never Beethoven after Chopin or Beethoven with Liszt! It doesn't fit. If you play Beethoven and Mozart, you need a filler, maybe Schumann. He is very classical: baroque, polyphonic, and strict, yet romantic, it fits in between. Strangely enough, Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff follow Schubert. They complement each other. If you play Schubert and Mozart, then it takes something away. It's no longer a balanced weighting. But Schubert and Rachmaninoff: both stay as they are."T. J.:"A few days ago, Rostropovich played Prokofiev's cello concerto op. 125 and after the break, conducted Tchaikovsky's Sixth."S. R.:"Prokofiev is E minor, Tchaikovsky is B minor... no, that doesn't work. Tonic, dominant... and you can't have Prokofiev first and then Tchaikovsky."T. J.:"My God, I didn't realize program planning was so hard."S. R.:"No, it's really easy, you just need to think a little bit."

I bring flowers and a tape recorder.

S. R.:"Shall we listen to Franck?"César Franck's piano quintet, the recording with Richter and the Borodin Quartet. The bare room gradually dissolves. The recording is incredibly intense, with incredible suggestive power. Richter listens motionlessly, radiating magical attention. Afterwards, silence. The tension slowly fades, and you return to the earth. I note that it feels as if not five people are playing, but only one single, truly universal soul. Moreover, it is the most moving recording I have heard in a long time.S. R.:(nonchalantly): "Yes, yes, a great composition. You can't really say which movement is the best."N. D.:"Well, the first one."S. R.:"No, the second and third movements are just as good."T. J.:"The first movement certainly covers the widest range of emotions. It goes from absolute hopelessness to emphasis, and then to prayer."S. R.:"Yes, it's just feeling. Franck composed purely from feeling. That's why the form is perfect."

T. J.:"Rachmaninoff is often somewhat ridiculed in Germany. Does he embody the stereotype of the 'Russian soul'?"S. R.:"And probably Tchaikovsky is ridiculed too, Ravel too, Puccini too... and Debussy too, yes yes (Richter laughs). Of course, Rachmaninoff wrote some bad music, that's true. For example, the Corelli Variations are banal, some of the smaller pieces are dreadful, like the Elegy. Terrible music (Richter shakes his head). The Paganini Rhapsody is actually a fantastic work, but I hate one moment in it: the last bar. The whole piece is good, just the ending, it's like... like nonsense, as if someone were spitting. (Richter hums the passage, looks questioning) Hm? Simply banal... Tchaikovsky also wrote bad music, but do you know why?"S. R.:"Because he had an incredible work ethic. He composed five hours every day, no matter what. Not everything can be good if you work like that... Also, why should I play the Paganini Rhapsody when the Paganini Variations by Brahms are the best? I play those; they are better than Liszt's, better than Schumann's. Do you know my recording of the second Rachmaninoff concerto with Sanderling? I like it, but something terrible happened. Do you remember how the piece starts? It starts very quietly. In the first chords, there's a c' in the soprano, and you know what? The first chord is missing the c'!"T. J.:"And you don't cut?"S. R.:"No, I obviously don't cut. (Richter is horrified). It was so quiet, no one noticed, not even me. And now it's in the upper voice, that's terrible. But still, it's the best work by Rachmaninoff. Do you know the first piano concerto?"T. J.:"Oh yes, I really like that piece. It has a somewhat morbid character, something of the fin de siècle, almost U-music."S. R.:"Yes, well, of course, it's a little sugary, but just like a very fine perfume can be sugary, this piece has incredible charm and nobility... sweet, but good."T. J.:"You said the second piano concerto is Rachmaninoff's best work. But the third is played much more often."S. R.:"Neuhaus described the concerto very well. He said it's like a rich landowner coming back to his estate. It's beautiful and grand, with so many rooms. Everything is magnificent. First, he goes into the first room, strolls around a bit, looks, walks into the next. It's just as beautiful, and the landowner examines it just as carefully, and so on. I've heard this piece a few times, even by lesser pianists – and somehow, they all play it decently. It's one of those works, somehow, I don't know why, it sounds good no matter who plays it."T. J.:"You've never played it."S. R.:"I've heard it so many times, and it was good. Also: The first theme, it's a bit of the 'Russian soul' cliché. I simply can't listen to this piece anymore. I can't listen to Chopin's b-minor sonata anymore, nor the h-minor sonata, or the Appassionata. I can't listen to all of that anymore. I played the Appassionata a lot, in 1960. But today, I'd rather play five new Haydn sonatas."

S. R.:"Once, I played the Jeunehomme concerto by Mozart. The conductor was very polite and sympathetic. But he was way too slow in the second movement. After the concert, Maazel came up to me and asked: 'My God, what did he do to you?' And the next day, the newspaper said: 'That was the Russian soul of the pianist.'" (Richter laughs)

S. R.:"Do you know, Rubinstein was a very happy person, I think... it radiated from every pore. Well, he lived somewhat carelessly, and you could hear that in his playing. He really practiced very little, but in the end, everything worked out for him. Only after his marriage did he start to work seriously. But before? He was a bit like 'meh' (Richter waves his arms absentmindedly). He was a very charming person and had an incredible success with women. And then he wrote memoirs, which were incredibly reckless... But I don't like reading memoirs, I prefer novels."N. D.:"Rubinstein once told me the following story: 'Everyone was talking about Richter. Well, I thought, I'll go and listen to this Richter. So I went. The playing wasn't bad, technically good, professional, everything was fine. But nothing special. But at some point, I caught myself, my eyes became wet, tears rolled down my cheek, and my heart squeezed.'"

S. R.:"Neuhaus had many female students who were very beautiful, but didn't play particularly well. Once, we listened to one of them together. After she had left, Neuhaus said, 'My God, this girl looks like the Venus de Milo, but why does she have hands?'"

T. J.:"A few days ago, Rostropovich played Prokofiev's Cello Concerto op. 125 and then conducted Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony after the break."S. R.:"Prokofiev is in E minor, Tchaikovsky in B minor... no, that doesn't work. Tonic, dominant... and anyway, you can't play Prokofiev first and then Tchaikovsky."

S. R.:"You know, Rubinstein was a very happy person, I think... it radiated from every pore. Well, he lived somewhat carelessly, and you could hear that in his playing. He really practiced very little, but in the end, everything worked for him. Only after his marriage did he start working seriously. But before? He was a bit 'meh' (Richter waves his arms absentmindedly). He was a very charming man and had an incredible success with women."

S. R.:"The only good things about America are the museums, the orchestras, the cocktails, and the movies. But otherwise, the country is not cultured. Besides, you have to fly there, and I hate that... and the dreadful English they speak, it's terrible!"